"Old Friends"

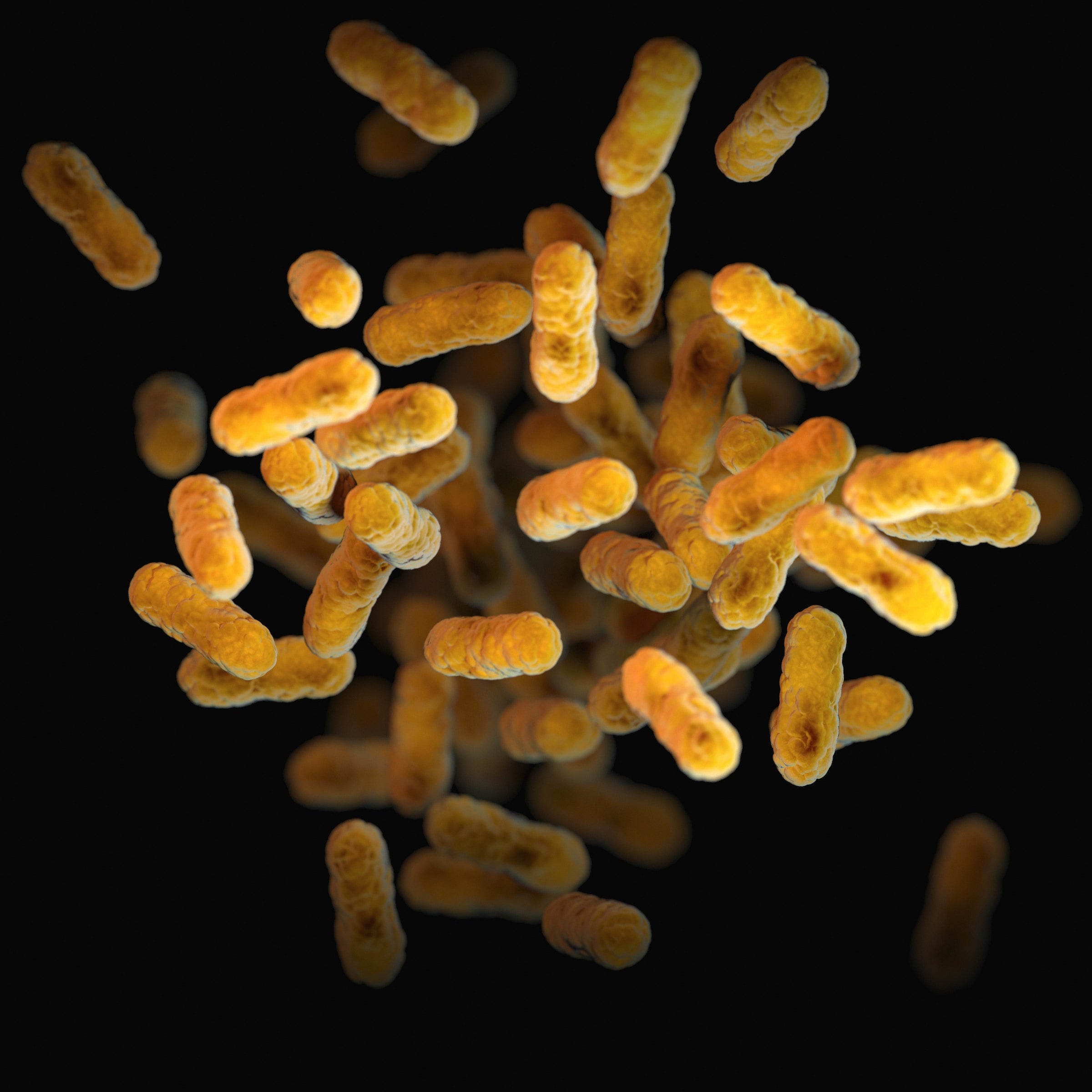

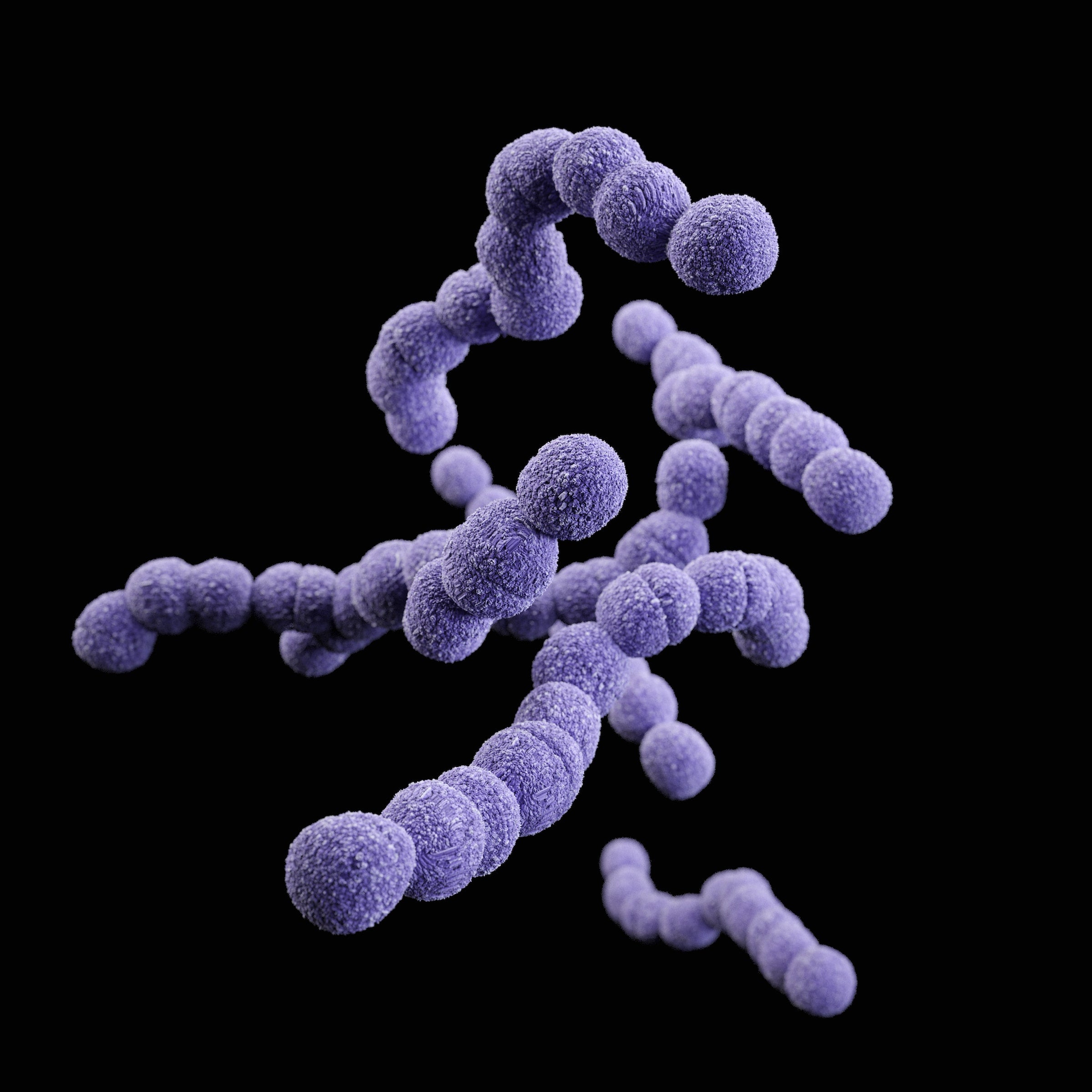

Researchers have called helpful bacteria like M. vaccae our "old friends" as we had frequent contact with these kinds of bacteria in the past that had beneficial impacts on our immune system and health.

Highlights & Summary

- The "Old Friends" hypothesis highlights our deep-rooted bond with beneficial microbes.

- We co-evolved with these microorganisms, forging a partnership spanning millennia.

- Modern lifestyles have inadvertently severed this essential connection.

- Our immune systems, shaped by these microbes, may falter without their guidance.

- Rekindling our relationship with our "old friends" could be crucial for optimal health.

- Recognizing & embracing this bond can unlock a deeper understanding of human well-being.

The "Old Friends" hypothesis, initially termed the "Hygiene Hypothesis", was proposed to explain the rising incidence of allergies and autoimmune diseases in developed countries. The crux of the idea is this: as societies become more urbanized and our lives more sanitized, we have distanced ourselves from the rich microbial milieu that was once an integral part of our environment. This disconnect is believed to have unintended consequences for our immune system.

Throughout evolution, humans coexisted with a vast array of microorganisms (like Mycobacterium vaccae). These 'old friends' were not merely passive passengers but played a vital role in shaping our immune responses. Regular exposure to these microbes ensured that our immune system was fine-tuned, capable of differentiating between harmful invaders and benign entities.

In the absence of these microbial interactions, our immune system becomes like an orchestra without a conductor—out of sync and prone to overreactions. Allergies, asthma, autoimmune diseases and even mental illness are manifestations of such immune dysregulation. The "Old Friends" hypothesis suggests that by reintroducing ourselves to these microbial companions, we can restore this balance.

At a glance, this theory serves as a poignant reminder of our intrinsic bond with nature. In our pursuit of cleanliness and progress, we've unknowingly severed ties with entities that have been our allies for eons. But the message here is not one of loss, but of hope and rediscovery. By understanding and embracing our "old friends", we can forge a healthier, more harmonious relationship with the world around us.

Just as we cherish and learn from old friendships in our personal lives, it's high time we recognized and celebrated the invaluable lessons our microbial friends have to offer. After all, in the grand tapestry of life, every thread, no matter how microscopic, has its unique role and purpose. The "Old Friends" hypothesis beckons us to reconnect with these threads, and in doing so, rediscover a vital part of ourselves.

The History of Our "Old Friends"

A Journey Through Time: Age-old Bonds and Newfound Understandings.

Prehistory

Prehistoric Times: Coexistence with Microbes

During the majority of human evolution, our ancestors led nomadic lifestyles, hunting and gathering their food. Living in close harmony with the environment, early humans had frequent and diverse interactions with a wide range of microorganisms from soil, water, plants, animals, and even other humans. This consistent exposure forged an intimate bond between microbes and the evolving human immune system.

10,000 BCE

Agricultural Revolution

With the dawn of agriculture, humans began to settle down, cultivating land and domesticating animals. While this led to more consistent food sources and the growth of civilizations, it also brought humans in closer contact with specific sets of microbes, particularly those associated with domesticated animals. Zoonotic diseases (those that jump from animals to humans) became more prominent. However, day-to-day life, from farming to food preparation, still entailed significant interaction with a diverse array of microbes.

3,000 BCE

Ancient Civilizations

As empires and cities grew, so did human understanding of sanitation and public health, albeit rudimentary. While practices like mummification by the Egyptians showed awareness of preservation and possibly a basic understanding of decay and decomposition, the concept of invisible entities (microbes) causing disease was not yet recognized. Still, daily life, whether in the bustling streets of ancient Rome or along the fertile banks of the Nile, ensured that humans remained in contact with nature and, by extension, a vast variety of microorganisms.

1675

Discovery of Microorganisms

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, using his homemade microscope, becomes the first person to observe and describe microorganisms, which he termed "animalcules." This is the dawn of microbiology.

1850s

Germ Theory of Disease

Louis Pasteur demonstrates that microorganisms cause fermentation and spoilage. Robert Koch postulates criteria (Koch's postulates) to prove that a specific microorganism causes a specific disease. This solidifies the germ theory, which posits that many diseases are caused by microorganisms.

1950s

Rise of Allergic Diseases

Industrialized nations observe a rise in allergic diseases like asthma, hay fever, and eczema. This trend would later lead researchers to question why these diseases are increasing.

1989

Introduction of the Hygiene Hypothesis

David P. Strachan proposes the "Hygiene Hypothesis" in a paper published in the British Medical Journal. He observes that children in larger families, who are presumably exposed to more infections early in life due to contact with siblings, have a reduced risk of developing hay fever, suggesting that infections during childhood might protect against allergic diseases.

2000s

Evolution of the Hygiene Hypothesis to the "Old Friends" Hypothesis

Researchers like Graham Rook elaborate on Strachan's original idea, suggesting that it's not just any microbes, but specific ancient microbes ("old friends") that humans have co-evolved with, which are essential for the proper training of our immune system. The absence of these microbes in modern urbanized settings is proposed to contribute to the rise in allergic and autoimmune diseases.

2010s

Microbiome Research Boom

Advances in DNA sequencing technologies enable detailed studies of the human microbiome (the collection of all the microorganisms living in association with the human body). Findings from these studies further support the "Old Friends" hypothesis by illustrating how changes in the microbiome can influence immune responses and disease susceptibilities.

Recent Years

Therapeutic Implications

Ongoing research explores how reintroducing or stimulating exposure to these "old friends" can have therapeutic benefits, leading to studies on probiotics and other microbiome-targeted interventions for allergic and autoimmune conditions.

Recent Years

Isolation and Study of Soil Mycobacteria

John Stanford isolates and studies strains of mycobacteria from mud in Africa and notices beneficial immunomodulatory effects. Research on these strains is continued by Angus Dalgleish, Charles Akle, Graham Rook, Christopher Lowry among others.

2023

Mycobac Introduces Müd+

Mycobac is founded and launches a supplement containing one of the more heavily studied strains originally isolated by John Stanford, Mycobacterium vaccae NCTC 11659. Clinical studies indicate the strain possesses beneficial qualities that may support mental health.

During the majority of human evolution, our ancestors led nomadic lifestyles, hunting and gathering their food. Living in close harmony with the environment, early humans had frequent and diverse interactions with a wide range of microorganisms from soil, water, plants, animals, and even other humans. This consistent exposure forged an intimate bond between microbes and the evolving human immune system.

With the dawn of agriculture, humans began to settle down, cultivating land and domesticating animals. While this led to more consistent food sources and the growth of civilizations, it also brought humans in closer contact with specific sets of microbes, particularly those associated with domesticated animals. Zoonotic diseases (those that jump from animals to humans) became more prominent. However, day-to-day life, from farming to food preparation, still entailed significant interaction with a diverse array of microbes.

As empires and cities grew, so did human understanding of sanitation and public health, albeit rudimentary. While practices like mummification by the Egyptians showed awareness of preservation and possibly a basic understanding of decay and decomposition, the concept of invisible entities (microbes) causing disease was not yet recognized. Still, daily life, whether in the bustling streets of ancient Rome or along the fertile banks of the Nile, ensured that humans remained in contact with nature and, by extension, a vast variety of microorganisms.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, using his homemade microscope, becomes the first person to observe and describe microorganisms, which he termed "animalcules." This is the dawn of microbiology.

Louis Pasteur demonstrates that microorganisms cause fermentation and spoilage. Robert Koch postulates criteria (Koch's postulates) to prove that a specific microorganism causes a specific disease. This solidifies the germ theory, which posits that many diseases are caused by microorganisms.

Industrialized nations observe a rise in allergic diseases like asthma, hay fever, and eczema. This trend would later lead researchers to question why these diseases are increasing.

David P. Strachan proposes the "Hygiene Hypothesis" in a paper published in the British Medical Journal. He observes that children in larger families, who are presumably exposed to more infections early in life due to contact with siblings, have a reduced risk of developing hay fever, suggesting that infections during childhood might protect against allergic diseases.

Researchers like Graham Rook elaborate on Strachan's original idea, suggesting that it's not just any microbes, but specific ancient microbes ("old friends") that humans have co-evolved with, which are essential for the proper training of our immune system. The absence of these microbes in modern urbanized settings is proposed to contribute to the rise in allergic and autoimmune diseases.

Advances in DNA sequencing technologies enable detailed studies of the human microbiome (the collection of all the microorganisms living in association with the human body). Findings from these studies further support the "Old Friends" hypothesis by illustrating how changes in the microbiome can influence immune responses and disease susceptibilities.

Ongoing research explores how reintroducing or stimulating exposure to these "old friends" can have therapeutic benefits, leading to studies on probiotics and other microbiome-targeted interventions for allergic and autoimmune conditions.

John Stanford isolates and studies strains of mycobacteria from mud in Africa and notices beneficial immunomodulatory effects. Research on these strains is continued by Angus Dalgleish, Charles Akle, Graham Rook, Christopher Lowry among others.

Mycobac is founded and launches a supplement containing one of the more heavily studied strains originally isolated by John Stanford, Mycobacterium vaccae NCTC 11659. Clinical studies indicate the strain possesses beneficial qualities that may support mental health.